Issue 11 of The Journal of the North American Japanese Garden Association (NAJGA), published in November 2024, features an article written by Will Lerner, Communications Manager for Portland Japanese Garden and Japan Institute. In it, Lerner shares insights from the organization’s Garden Directors and Curators, all Japanese-born niwashi (garden masters). They discuss the Natural Garden, one of the organization’s five historic garden spaces, and an example of the zoki no niwa style. To purchase a copy of this scholarly journal, visit NAJGA’s website.

By Will Lerner

In the first part of the 20th century, Hungarian scientist-turned-philosopher Michael Polyani delivered a series of lectures on something named the “tacit dimension.” This idea he put simply forth: “we can know more than we can tell”.1 What he meant is that there is a reservoir within us of knowledge that lays beyond our articulation. It is an intuitive concept. We can so easily picture a loved one with just a mention of their name. However, most of us would likely be unable to describe this same person in a way where someone else would. This suggests there is a “knowing” within us we often cannot express. Perhaps that’s why some art resonates with us—it feels as though its creator(s) have somehow ferried their passions to us so evocatively that we can call them our own. The Natural Garden in Portland Japanese Garden does just that. It is highly rustic and yet impeccably designed, paradoxically entirely natural and entirely artificial. It is made even more special by the fact that it is an art fostered over generations by multiple people; an intuition first shared, made recognizable, and then carried forward.

The Natural Garden is the fifth historic space in Portland Japanese Garden and was built in the 1970s after an initial moss garden in its space had failed to thrive in the way its builders intended. The other four spaces built in the 1960s, the Tea Garden, Flat Garden, Sand and Stone Garden, and Strolling Pond Garden, derive their aesthetics from eras that pre-date the Meiji Period (1868-1912). The Natural Garden is relatively recent, a style that has its roots in a reaction to the industrialization of Japan and, later, the devastation of World War II. Because so many Japanese gardens across North America have landscapes inspired by designs before the 19th century, the Natural Garden of Portland Japanese Garden is a unique joy to be immersed in.

The space is approached by walking a long and narrow path that slopes down by a hillside of matcha-green moss and a small and humble stone carving of a jizo, a Buddhist figure seen as a protector of travelers and children. After passing through a wooden gate with asymmetrical doors (one wide, one narrow), new lands are unveiled. Maples are delicately layered over gentle waterfalls, languid ponds, and bubbling streams. A series of winding stairs takes visitors past camellia and rhododendron. Interestingly, there are stone lanterns within, but most are so inconspicuous that they may fail to catch the eye. Two areas with long wooden benches hug its side before the path winds to a machiai (sheltered waiting area) that showcases the depth of the space and treats listeners to the sound of coursing water. Finally, an ascent through azaleas takes one by a distinctly different karesansui (raked gravel garden) before it places people on pathway adjacent to a pavilion.

The Natural Garden’s style is known as zoki no niwa (雑木の庭) in Japanese. While this literally translates to “natural tree garden,” it does not quite capture its essence. Looking at the words that join to create the Japanese appellation helps provide some insight. Within the context of a garden, zoki means anything that is not a tree that is maintained to be kept at human scale—its “opposite” being niwa ki, a garden tree. However, because it is a niwa, or garden, we reveal the paradox—the trees here are maintained and kept to natural scale, but in a manner that makes them look as though they have been untouched.

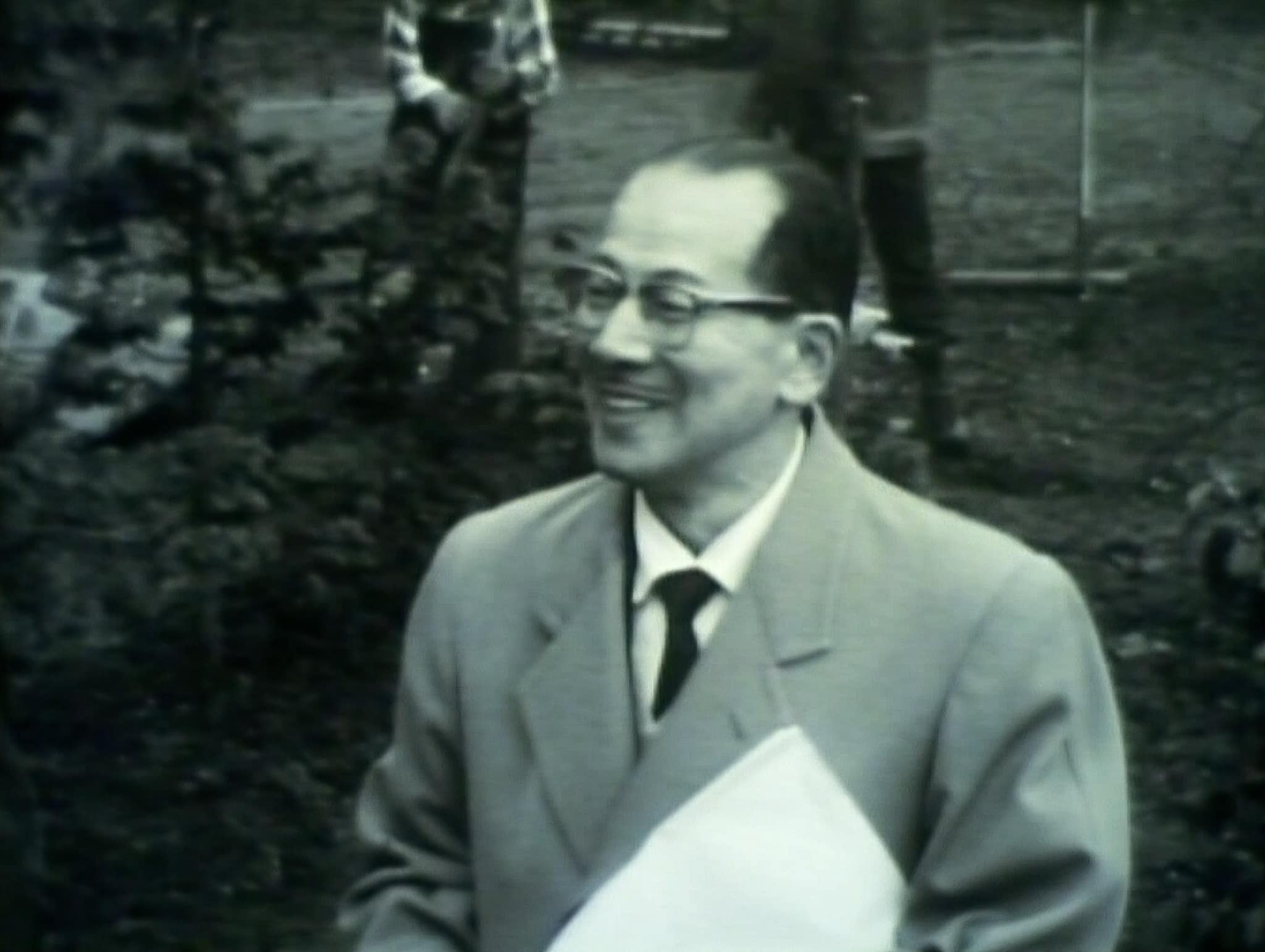

The aesthetics of zoki no niwa can be traced directly to two influential figures in Japanese landscape architecture in the 20th century: Kenzo Ogata (1912-1988) and his mentor Juki Iida (1890-1977). Both Ogata and Iida were known figures in the United States, with Ogata having worked on sites such as the East-West Center at the University of Hawai’i.2 Iida created more than 1,000 gardens but most have not survived—Seattle Japanese Garden is one of the few of his designed works that still exists today.3

The Moss Garden Before the Natural Garden

Initially there was no Natural Garden in Portland Japanese Garden. Professor Takuma Tono of Tokyo Agricultural University envisioned four garden styles when he was retained by the Japanese Garden Society of Oregon in the early 1960s to design its landscape in Portland’s Washington Park. Later into his tenure he was asked to design a fifth one: a moss garden.

The idea of building a moss garden was met with Tono’s approval. In a letter he wrote to the Garden’s Board of Trustees President Warren Munro in 1967 he noted that a “moss garden would be very interesting and unique in the States.” He sketched out the location he felt best for it, beside a karesansui (the Sand and Stone Garden), noting “this is [a shady] and [a] good place for cultivating moss.” In later correspondence with the organization, he acknowledged the difficulty in fostering such a landscape, cautioning, “One cannot expect such [gardens to be] successful from the [beginning]. Even in Japan there is just only one at Kyoto.”

The organization would find that the moss garden as it was constructed back then was not thriving in the way they had hoped. William “Robbie” Robinson, head gardener for Portland’s Parks and Recreation Bureau in this era recounted in a 2010 interview with Portland Japanese Garden Board of Trustees President Ed McVicker (2009-11) that the mosses, brought in from mountain ranges in the area, got overrun by wildlife. “The birds were taking the [the moss], flying away with them, [using the] mosses for their nests,” Robinson shared. “Other animals that were on the ground were tearing it up, looking for worms and different things. So, they had to give up the little Moss Garden.”

The Natural Garden would take its place under the guidance of Hachiro Sakakibara, the third Garden Director of Portland Japanese Garden (1972-74) and a student of Ogata. His predecessor and friend, Hoichi Kurisu (Garden Director, 1968-73), recalls that he and Sakakibara recognized the Moss Garden was failing and that a new course of action was needed. “When Sakakibara san arrived, he also thought that there had to be something done to the Moss Garden, and we talked about what we could do,” Kurisu told McVicker in 2010 when the former garden directors of Portland Japanese Garden returned for a reunion. “I remember that we then showed a design we proposed at the Board meeting but we never got a response of whether we would be allowed to do it or not. By that time, Sakakibara san was officially hired at the Garden and since the board never gave a clear answer, I remember him going in and asking for an answer. The Board finally decided to approve this project. It is a natural-style garden that we implemented.”

By the time the Moss Garden was undergoing its transition into the Natural Garden, Professor Tono’s contract had ended with Portland Japanese Garden. Nonetheless, Sakakibara says Tono supported the transformation. “Both Professor Tono and Ogata sensei played an important role in the landscaping world, which allowed them to become very close,” Sakakibara pointed out to Ed McVicker. “Also, by that time, zoki no niwa had become a mainstream style of garden in Japan. Professor Tono himself had also designed and built a zoki no niwa. I believe that he trusted me because he approved of the zoki no niwa and because of the underlying trust between Ogata sensei and him.”

A Reflection of a Lineage of Garden Directors

Hachiro Sakakibara is credited as the individual most responsible for building the Natural Garden that is enjoyed by hundreds of thousands of guests at the Oregon attraction every year. “The creator [of the zoki no niwa] is actually Ogata-san’s master, Juki Iida,” Sakakibara recounted to McVicker. “Later, Ogata-sensei introduced the zoki no niwa into public spaces such as parks, spreading it nation-wide. Now, zoki no niwa has become a mainstream style of garden. [It] incorporates the natural landscape rather than having man-made elements like the…old historical gardens in Kyoto. In Japan, the landscape is reflected in the zoki no niwa.”

Kurisu was also a student of Ogata and is well familiar with the origins of the Natural Garden Style. “[Iida and Ogata] were strongly impressed when they saw the Musashino wooded area, a small area in the Kanto Plain,” Kurisu told McVicker. “They believed that it had an amazing beauty to it and captured the essence of nature. They thought that it would be a great idea to incorporate that in a garden.”

Of the ten Japanese-born garden experts to have led Portland Japanese Garden through its more than 60 years of existence, five were students of Ogata. Toru Tanaka, the eighth Garden Director (1988-91) in this lineage, was among them. “It is not about being naturalistic but it’s about bringing the actual nature into the garden,” Tanaka shared with McVicker. “They introduced a new definition of beauty. Unlike the Kyoto-style gardens, in which each individual tree is carefully tended, a natural-style garden is concerned with the overall effect and the feeling you get. The introduction of this new style of garden was revolutionary for the history of landscaping and changed the general perception by bringing in the nature itself.”

Takao Donuma, another student of Ogata and the seventh Garden Director of Portland Japanese Garden (1985-87), helps illustrate the Natural Garden’s qualities by comparing it to the other four, more highly-articulated garden spaces. “I think that the focus in the four [other] gardens is to look and enjoy,” Donuma said in conversation with McVicker. “The modem zoki no niwa focuses on ‘feeling’ the garden and feeling embraced by the garden. It is more of a garden that is there to be used…a zoki no niwa does have ponds, stones, steppingstones, and azumaya (rustic hutches) that are elements seen in other gardens, but I think the difference is felt when you walk into the zoki no niwa and feel relaxed and peaceful.”

The fifth student and thus far unnamed student of Ogata to be Garden Director of Portland Japanese Garden is Michio Wakui (1974-76). “Probably the Flat Garden is the complete opposite style from the zoki no niwa,” he said, echoing Donuma’s thoughts. “The best part of the zoki no niwa is in its softness. Enjoying the softness of the trees and its branches and enjoying the changes in all four seasons is what a zoki no niwa is about.”

Hugo Torii has served as Garden Curator for the organization since 2021. In explaining the Natural Garden, he points to a 1973 book penned by Ogata, Sakuhin-shu Niwa, Shizen to Zokei (Literally, “Collected Works: Garden, Nature and Form”). Torii notes a passage in which the niwashi (garden master) gives guidelines for residential gardens that provide insight on the philosophy of natural gardens: “Ogata reminds us that those making residential gardens should be conscious that they’re making a living space. They should be aesthetically pleasing but also calming and provide space to heal from the stress of a restless world.”

Torii also points to how Iida and Ogata, both well into adulthood by the time WWII occurred, were informed by the breakneck development Japan underwent after the Edo Period (1603-1868). “Rapid industrialization had a great impact on how the Japanese valued gardens,” Torii shares. “The aftermath seemed to be a growing demand for the preservation of green spaces and the healing of nature. Gardeners were concerned that people were becoming further distanced from the natural world.”

Aside from the more philosophical qualities of the zoki no niwa, there was a practical reason for its emergence as a garden style—its affordability. “As you know, in 1945 when WWII ended, Japan had nothing left and had to rebuild everything from scratch,” Kurisu commented to McVicker. “The Japanese people had no money but I think they still wanted Japanese gardens. … In addition, since this new style of garden uses native plants, zoki, it was a low-cost garden compared to traditional gardens that used expensive pines. Juki Iida sensei and Kenzo Ogata, therefore, combined native trees and the traditional Japanese garden techniques to create the zoki no niwa.”

“People were trying to heal from the War, longing for a place to heal,” Kurisu continued. “And the garden that was created to respond to the longing of these people. I think, [that comes with] the zoki no niwa. It’s a very gentle form of garden. I remember that it took my breath away when I first visited a zoki no niwa after I returned from the U.S. It was May, when I returned, and the sun came through the branches of the trees, glistening on the surface of the flowing stream. It felt like being in a different world and I think that the zoki no niwa is a garden that pursues that feeling.”

Part of what helps conjure this feeling Kurisu mentions are gardening techniques that are tailored to the space. Torii shares that part of the approach taken is illustrated by Iida Juki Teien Sakuhinshu, or “The Gardens of Juki Iida,” published in 1980 by Garden Society of Japan (Nihon Teien Kyokai). “IIda used the term no-zukashi (野透かし); a specialized pruning technique for his natural gardens,” Torii offers. “The guidance provided is that one should prune according to a plant’s natural form and character. You don’t only work from the outside to make branches shorter, you use degawari (出替り), meaning a ‘switching branches technique’ to maintain their size. The same is applied for mid-sized and smaller-sized plants as well. No-zukashi is one of the most difficult pruning styles to work on trees; it has to be as if all the branches were removed by nature instead of the hands of gardeners.”

Every garden space in Portland Japanese Garden is special and deeply meaningful in their own right. But perhaps the Natural Garden is the most deeply tied to the organization’s history, itself a reaction of sorts to World War II. Portland and its state of Oregon were hostile environs for those of Japanese ancestry ever since those from the archipelago nation first settled here in the 19th century. During WWII, conditions reached a sickening, dizzying new height of animosity when many in power urged for their banishment to concentration camps and fought against their return. Portland Japanese Garden was founded because of a grassroots effort catalyzed by those of Japanese descent and their allies in various cultural organizations and civic and government leadership to help repair the fractured relationship and move forward together in harmony and peace through nature.

Japan’s greatest dramatist, Chikamatsu Monzaemon, once noted, “Art is something which lies in the slender margin between the real and unreal.”4 While he was discussing bunraku (puppet theater), this perspective perhaps also captures the joyous beauty of the Natural Garden—a liminal space that looks like it has been dreamt rather than built by hand. Of course, as Polyani might note, expression of its virtues can only do so much to lend understanding. If one truly wants to know the Natural Garden, they must visit the Natural Garden. Portland Japanese Garden is ready to receive you.

Works Cited

1 Polyani, M. (2009). The tacit dimension. The University of Chicago Press.

2 East-West Center. (n.d.) About EWC: Japanese garden. https://www.eastwestcenter.org/about/japanese-garden

3 Kennedy, C. (2017, February 14). A quiet legacy: The Juki Iida scroll. https://www.seattlejapanesegarden.org/blog/2017/2/14/cjy4gju7a7svo3205d23wl7rfmganu

4 Keene, D. (1981). Appreciations of Japanese culture. Kodansha International.