Written by Will Lerner, Communications Manager for Portland Japanese Garden & Japan Institute

Kintsugi Expert and Master Conservator Transforms Trauma into Beauty Through Her Work

Please note: This article mentions a topic that may be difficult for some to read, namely domestic violence.

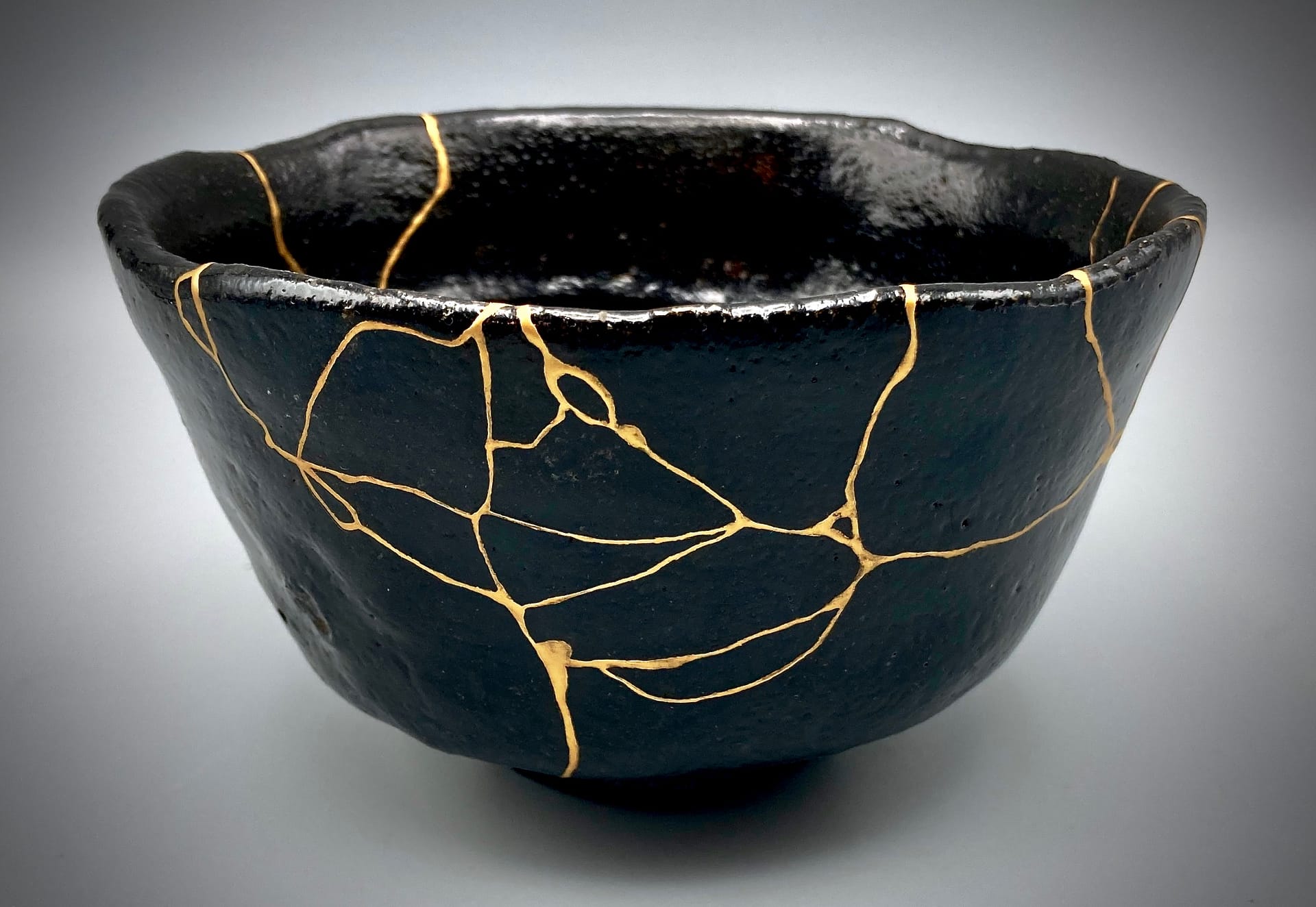

On September 28, Portland Japanese Garden debuted its final art exhibition of 2024, Kintsugi: The Restorative Art of Naoko Fukumaru. In both the Pavilion and Calvin and Mayho Tanabe Galleries, the show will feature the artwork of kintsugi artist and master conservator Naoko Fukumaru. “Kintsugi is a five-hundred-year-old Japanese method of restoring damaged ceramics with natural urushi lacquer dusted with powdered gold, seen as enhancing beauty by celebrating imperfection and impermanence,” shares Fukumaru, as the story notes below.

On an overcast and chilly December day in 1962, crews of workers and their bulldozers arrived to a lofted hillside in Washington Park in Portland, Oregon’s West Hills. Once home to the Portland Zoo, the grounds these laborers arrived to was broken. Except for a few decrepit buildings still standing, it was a landscape in ill health. City Commissioner Ormond Bean was on hand to supervise the removal of four feet of poor soil from a spot that, in clearer conditions, would have an unimpeded view of Mount Hood. Bean, by now a longtime member of Portland’s government, had been working with then-Mayor Terry Schrunk to take this discarded land in a new direction. The leaders negotiated the lease of this perch and the five-and-a-half acres surrounding it to a burgeoning organization: the Japanese Garden Society of Oregon.

Today, this spot is now known as the Flat Garden of Portland Japanese Garden. Next to the Pavilion, raked gravel and stone lanterns are accompanied by shore and black pines, maples, and a weeping cherry that alights in neon pink in spring. This authentic vision of Japan was not helicoptered in from Kyoto. The vessel that contains this beauty is the same land that was once so bleak only 60 years ago. The difference is that it was enhanced—the cracks and flaws filled with plant and stone. It is in this we can glean what is so captivating and inspiring about the Japanese art of kintsugi.

“Kintsugi is a five-hundred-year-old Japanese method of restoring damaged ceramics with natural urushi lacquer dusted with powdered gold, seen as enhancing beauty by celebrating imperfection and impermanence,” shares Naoko Fukumaru. Fukumaru is a kintsugi artist and master conservator with more than 20 years of experience as a professional ceramic and glass conservator who has worked with the Detroit Institute of Arts Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and other institutions in the U.S., Europe, Egypt, and Japan. In September, her exhibition, Kintsugi: The Restorative Art of Naoko Fukumaru debuted at Portland Japanese Garden.

The Creative Influence of Kyoto

Fukumaru was born and raised in Kyoto, a city with cultural output that has influenced Japan and the world for centuries. “I was so fortunate to be raised in a in a city surrounded by temples, shrines, gardens, traditions, and cultures,” she shares. “Growing up in Kyoto strongly influenced my artistic and creative sense.”

Among the many charms of Japan’s ancient capital city are its many family-owned businesses, some of which have been operated by successive generations dating back decades and even centuries. Fukumaru’s family is among them. “My grandfather, Shozaburo Fukumaru, started our family’s antique auction company in 1912,” she notes. “In order to be who I am now; it was essential for me to be born into this family and our business. I was immersed in art, antiques, traditions, and our culture. My father, in particular, taught me so much.”

A childhood steeped in the rich and diverse arts of Kyoto permeated Fukumaru’s worldview and her appreciation for the arts extended beyond Japan’s borders—she has studied and practiced 25 years of the Western approach to hidden restoration. Fukumaru made her first repair, however, before receiving any formal schooling.

“When I was around eight years old, I fixed my mother’s tangled necklace,” Fukumaru recalls. “My mother had already spent hours trying to fix it, but she couldn’t, so I helped her. She was amazed at how I could untangle it easily, which made her happy. After that, I was willing to fix things when something got broken at home. It was inspiring that my efforts transformed unusable into usable, and beyond that, could make people happy.”

However, the unfortunate patriarchal qualities still too present even in modern Kyoto, led Fukumaru to leave home when she was 19. “Women are not expected to reach a high level, and male children are more important than female children in families with businesses,” she shares. “It was necessary to leave Japan to find my true self.”

A Transformation of Suffering into Something Beautiful

Kintsugi itself would not capture her full attention until she settled in Vancouver, British Columbia. “I moved to Canada about five years ago,” Fukumaru shares. “I was at the very bottom of my life—my marriage of 21 years had broken down and I was experiencing domestic violence. Despite this, I was hesitant to leave because I had two children. But after some time in Canada, my mind began to change. The beautiful nature and its honest and caring people helped me realize I shouldn’t be an unhappy mother and that violence shouldn’t be tolerated. I decided to flee to a women’s shelter. I thought things were going to get better. The physical violence ended, but the grief and trauma kept coming like big waves, one after another. I was in a dark place even after I left the shelter.”

“But then kintsugi came into my life,” Fukumaru continues. “I received a mysterious email from a local potter stating, ‘I am sorry that I missed your kintsugi workshop, and I want you to put me on the list for the next workshop.’ I was like, ‘What?’ I had never given any workshop, and I didn’t know how to do kintsugi. But then I thought about the 25 years of experience I had as a ceramic restorer and was sure I could learn the Japanese way and even teach it to others. My father sent me a big box of books about kintsugi. I was reading and reading and reading for six months.”

“I had long known of kintsugi, but until this point, I was not broken enough to fully understand its beauty and philosophy. Now I was so broken. I immersed myself into the metaphor of kintsugi and how it was beautiful. Often discarded and hidden away, imperfect things are considered to have diminished value. But brokenness is part of our history and flaws are integral parts of our identity; elements that shape our uniqueness. By magnifying imperfections in objects, these works lead us to accept fragility and imperfection in ourselves and in life. Kintsugi also acknowledges the life cycle of the objects, potters, and mistakes to allow the person to move on.”

“It was very painful to face what I had experienced, and I could not touch my wounds,” Fukumaru continues. “After three years of my healing journey, I was able to face my trauma and find a healing path that transformed my pain. My artwork involves a lot of effort, energy, and time, but the result is very powerful, a transformation of my suffering into something beautiful.”

Kintsugi Artist or Ceramic Therapist?

Kintsugi is not an easy artform to pursue, let alone master. However, because of the more than two decades Fukumaru had spent in restoration, her upbringing in a family of antique experts, and the intensive studying she underwent, she was able to pick up the nuances more quickly and assuredly than someone who is starting from scratch. That said, regardless of her experience, creating kintsugi is a long and patient process. It is not surprising that she devotes a considerable amount of thought to her work before any lacquer is applied. “I spend a long time with each ceramic, communicating and listening to how they want to be transformed,” she shares. “Some are conservative, and some are challenging and thought-provoking. More than restoring that which is physically broken, I am restoring the broken spirit of the ceramics.”

Fukumaru will often make use of broken ceramics from her family’s auction house in Kyoto, all carefully selected by her father and brother. However, part of what makes Fukumaru’s art so captivating is that she also applies kintsugi techniques to pieces that aren’t Japanese in origin. “My work respects the traditional materials and aesthetics of kintsugi but also innovates beyond convention to include pieces belonging to all cultures and eras,” she says. “I try to have an uninhibited and instinctive approach inspired by a cross-cultural celebration of imperfection. Through this, I intend to raise the interconnected nature of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender.”

“Sometimes I metamorphosize from a kintsugi artist into a ceramic therapist, transforming trauma into beauty. Ceramics are very close to our life; we use and touch them every day. Sometimes they become like friends or family—there can be many lingering emotions associated with a damaged piece. I spend several months restoring each ceramic with care and love. When the owners are reunited with kintsugi-restored ceramics, they are amazed at the transformation. Many tell me, ‘Wow, this is more beautiful than when it was complete. I am happy that the ceramic got broken.’ To me this is extraordinary. I never heard this compliment in all my 25 years doing hidden restoration.”

An Ideal Place to Hold a Kintsugi Exhibition

The Restorative Art of Naoko Fukumaru will be on display at Portland Japanese Garden when it undergoes a dazzling transformation of the seasons—the last vestiges of summer green will be consumed by ruby red leaves in fall, and then, as the show reaches its conclusion, the white mists and fogs of winter. Fukumaru is excited to have her work accompanied by this awesome display of nature and for it be displayed in a Japanese garden. “My first job was cleaning my father’s little Japanese garden at our family’s auction house,” the artist recalls. “I started when I was eight years old, and I spent endless time in the garden—it became my safe place.”

“I started researching Portland Japanese Garden because it is the most beautiful and authentic Japanese garden in the world outside of Japan,” Fukumaru continues. “I discovered that the organization’s intention was to heal the wounds of World War II by creating a garden designed to bring a better understanding of Japanese culture to Portland. I was fascinated and drawn into Portland Japanese Garden even more after learning this—it’s an ideal place to have a kintsugi exhibition.”

The years following World War II in Oregon was one remarked by an urgent need of restoration. A jewel of its home city for more than 60 years, Portland Japanese Garden represents the incredible potential of transformation. A ruined landscape was mended. A divided community saw the gulfs between them lessened. The Garden shows that broken places, people, and things can still broker peace, beauty, and hope—all it takes is someone who is willing to put things back together. Someone like the Garden’s founders. Someone like Naoko Fukumaru.

“I resonate with the mission of the Portland Japanese Garden, [Inspiring Harmony and Peace],” concludes Fukumaru. “I put broken fragments back together, sometimes in harmony with other materials, ages, and cultures. By doing so, I include my message that we can all work together to bring healing and peace to the world. I sometimes challenge the world by not placing the fragments in their original positions, exposing large losses and broken edges, adding unusual materials, or drawing designs. My challenges provoke vital discussions, force viewers to question their own beliefs, and spark social dialogue around important issues. Despite the challenges and distractions in life, the ultimate goal is to learn love, peace, and harmony through multiple lifetimes, leading to a future where the purpose of humanity lives in unity.”