An Introduction

Portland Japanese Garden is often referenced as “more than a garden.” What does this mean? Beyond the serene spaces, the Garden is a non-profit, cultural institution that allows visitors to experience Japanese culture through its events and programs. This allows the Garden to be a representation of cultural diplomacy–the act of sharing one’s cultural gifts to evoke peace and human connection.

The Garden just celebrated its 60th anniversary last year. To have gone from a post-World War II landscape of hostility to a flourishing garden that doubled in size within a generation is nothing short of remarkable. Portland Japanese Garden began with a seed of hope and healing but its reason for existence started even before that. To understand the full story of Portland Japanese Garden is to know the context in which it was established.

As we celebrate Asian American, Native Hawai’ian, Pacific Islander (AANHPI) Heritage Month in May, we reflect on what it means to be an organization that represents this community by diving further back into our history. The experience of Oregon’s Nikkei (the Japanese diaspora) has been filled with triumph and accomplishment. It has also been rife with tragedy and turmoil. Despite the best efforts of the Issei (first generation Japanese immigrants) and Nisei (second generation) to live the American dream as so many others have and will, they were often marginalized, assaulted, and incarcerated simply because of who they are. The battles they endured were not so long ago–and while there has been progress, the path to equity continues to be paved today.

As a Japanese American mother in Portland, I feel fortunate, inspired, and reassured knowing that a place like Portland Japanese Garden exists, where I can bring my children to connect to our heritage in a setting they love–nature! I’m grateful to share the opportunity to learn more about the Japanese experience in Oregon so that together, we can help create an ever more harmonious and vibrant community for generations to come.

– Megumi Kato, Director of Marketing (Nisei)

1832-1834: Shipwrecked in the Pacific Northwest

On October 11, 1832, a 14-person crew stocked a ship with rice and ceramics and other tributes from the Owari clan for Tokugawa Ienari, the eleventh Tokugawa shogun of Japan. Leaving Toba Port in Mie Prefecture, the Hojun-maru set sail for Edo (today known as Tokyo). Calamity would soon prevail itself upon these seafaring men when a typhoon snapped their vessel’s rudder and knocked them off course. The Hojun-maru would not only never arrive on Edo’s shores, it and nearly all its crew would never see Japan again. Subject to the whims of the mighty Kuroshio, an ocean current that has a flow of water equal in volume to 6,000 rivers, the ship drifted further and further east. Meals of rice and rainwater could only provide so much nourishment; the seamen would begin to die of scurvy.

Finally, in May of 1834, the Hojun-maru and its surviving crew, one man named Iwakichi and two teenage boys, Otokichi and Kyukichi, ran ashore on Cape Flattery. Here on the furthest northwestern point of the United States before Alaska, they would become the first known Japanese individuals to step foot on Pacific Northwest land. Thousands of miles away from home in an alien land, their initial experience in North America would be one of subjugation. The indigenous Makah people discovered these wayward souls, took their possessions, and enslaved them. When word of the castaways reached Fort Vancouver’s Chief Factor, John McLoughlin, he arranged their rescue and tended to their care before unsuccessfully attempting to leverage them in trade negotiations with Japan. Of the three, only Otokichi’s fate is known. Unlike his compatriots, he would see Japan again but declined an opportunity to repatriate to his native land, living the rest of his days in Singapore.

The cruelty of Iwakichi, Otokichi, and Kyukichi’s conditions, the unkind treatment from their hosts and the indomitable spirit it must have required to persevere despite it all would become a common shared experience of Japanese immigrants and their progeny.

1880-1907: A Community Grows in Oregon

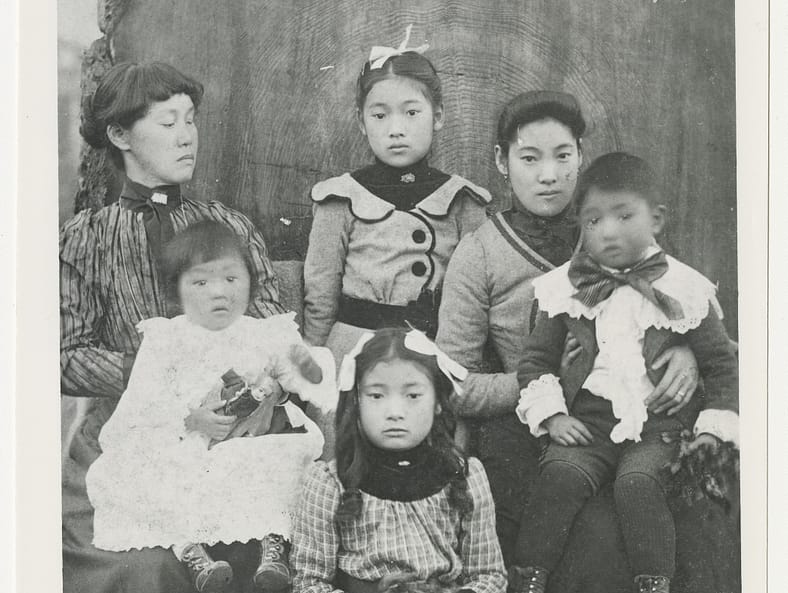

In 1880, Oregon would receive its first Issei, or first-generation Japanese immigrants: Miyo Iwakoshi, her brother Riki, and daughter Tama. Iwakoshi and her partner, an Australian-Scottish professor named Andrew McKinnon, would open a mill in Gresham named “The Orient.” When McKinnon passed away only a few years later, Iwakoshi would have to overcome the adversity of being left to fend for herself in a frontier state and she did.

Iwakoshi earned notice for demonstrating that silkworms could produce silk in Oregon and her knowledge of the area and her willingness to help others would lead her to becoming known as the “Western Empress” to Oregon’s Japanese community. Her daughter Tama would wind up constituting half of the state’s first Japanese marriage when she wed merchant and labor contractor Shintaro Takaki later in the decade.

It was a time of growth for the population of Oregon’s Issei. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, a federal piece of legislation that forbade Chinese immigration to the United States, had left employers with less workers to exploit. With Japan experiencing the rocky Meiji era (1868-1912), some of its population would seek stability and maybe even fortune across the Pacific. They would be welcomed by railroads, logging outfits, and agricultural endeavors. Paid less than their fellow immigrants from Europe, the early years for the Japanese laborer were tough going; often they could only find shelter in freight cars, barns, and tents. Some would even have to resort to living in caves.

It was in these early years those of Japanese ancestry here in Oregon would demonstrate gaman, or “strength, endurance, self-discipline, an awareness of others, and the ability to keep the future in sight.” The ability to tap into gaman would be required of them. Because of this reserve of fortitude, many of the area’s Issei would begin to thrive.

Toward the end of the 19th century, Portland’s Japantown, or Nihonmachi, developed in what today is known as the Old Town neighborhood, a curve of the earth in the northwestern part of the city that touches the Willamette River. A combination of racism that prevented their free movement across the city and surely their own desire to build community with those with whom they shared a common background, the streets between 1st and 6th Avenues would see the establishment of Japanese-owned hotels, restaurants, barbershops, and other businesses. By 1900, Japan would open a consulate office in Oregon to serve the 2,500 Issei who were now living here.

In 1907, one of Oregon’s earliest and most successful Issei, labor contractor Masuo Yasui, started to establish himself as a leader of his community. In pursuit of donations for a Japanese float in a Rose Festival Parade, Yasui’s journeying took him out to Hood River, a small but growing town nearly 60 miles east of Portland along the Columbia River. The beauty and fertility of the lands here would dazzle Yasui, who would go on to persuade his brother Renichi Fujimoto to join him in opening Yasui Brothers General Store in the town. Yasui would soon become an advocate for Japanese immigrants to stay in the area, befriend their white neighbors, and live the promise of the American dream. Putting money where his mind was, Yasui purchased 320 acres of Hood River farmland and would give his fellow Issei interest in it, paving the way for them to become landowners in their own right. The area would join Portland as another significant Japanese enclave in the Beaver State.

1910-1940: An Increasingly Hostile Landscape

The early 20th century saw increasing tension between the governments of Japan and the United States. Japan, which had been forced into a relationship with the U.S. after being subject to the western nation’s gunboat diplomacy in 1854, had started to grow in stature as a world power. Following Japan’s victory in war with Russia in 1905, concerns of their own possible battle with Japan weighed heavily on the minds of American leaders. When the San Francisco, California Board of Education declared Japanese students would be segregated from white ones in 1906, an international crisis erupted. To avoid further conflict, Japan and the U.S. would enter into an agreement in which Japan agreed to reduce the number of people allowed to emigrate east in exchange for the end of Japanese segregation in the U.S.

While this compromise would lessen the ability of the male Japanese laborer to move to the American Pacific coast, an exception for parents, wives, and children of current residents led to an increase in the Japanese population of Oregon nonetheless. From 1910 to 1920, the number of Japanese women in the state would increase more than 400%. Families developed, and the number of Nisei, or second-generation Japanese would begin to grow.

In the early years of the 20th century, racism toward the Japanese here gained momentum and power. Despite a population that was relatively tiny compared to those who were white, those in the halls of Oregon’s power would deride their neighbors and fellow Americans, espousing the tenets of the fascist playbook in which a minority group is demonized and blamed for society’s woes. As early as 1907, the Oregon Bureau of Labor would advocate in a report that further restrictions on Japanese immigrants should be set in motion, referring to the Japanese as a menace to the white worker. In 1909, The Oregonian published an opinion article that spewed hatred towards a white woman who planned to marry her Japanese fiancé in Oregon, noting, “… the mere suggestion of such a marriage creates infinite disgust. Evidently the daughter who entertains it and the mother who supports it are religious and social perverts, who enjoy the notoriety.”

In 1917, one of the earliest anti-Japanese bills was brought forth in Oregon’s legislature. Senator George Wilbur of Hood River introduced Senate Bill 61, a law that would have prevented Japanese-born individuals from purchasing land. Obviously morally and ethically wrong, the reason it failed to advance was for economic reasons—organizations such as the Portland Chamber of Commerce and U.S. State Department worried it would tarnish commercial relations with Japan. Unfortunately, Wilbur was not the only one of his peers who sought to codify their bigotry. In 1919, Representative Chris Schuebel of Oregon City would attempt to ban land ownership by the Japanese, and like Wilbur, was mostly stymied for the fear of monetary loss.

Those with enough influence to roadblock land ownership laws did not articulate with any kind of passion the real reason these bills were bad: they were amoral assaults on a community’s collective personhood. Because there existed no coalition with enough cache to effectively articulate the simple point that racist laws are bad because they are racist, the Oregon legislature was able to pass feckless pieces of paper that had no real power but did assault the emotions of its Japanese constituency. In 1920, both the Oregon Senate and House of Representatives unanimously adopted a proposal that encouraged the alteration of the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution so that American-born children of immigrants would be ineligible for citizenship. That year the legislature unanimously passed Senate Bill 28, which would have banned immigrants deemed ineligible for citizenship, i.e. the Japanese, from being employable for public works projects. It wound up failing when Governor Ben Olcott did not sign it.

The 1920s was one in which Oregon, a state founded with white supremacist values when it incorporated the exclusion of Black people in its constitution, saw a surge in power from the Ku Klux Klan. The KKK would see as many as 25,000 members among its ranks in Oregon alone by the end of the decade. These Klan members were not just the rural poor, but state legislators, local government officials, members of law enforcement, and influential businesspeople. Their violent hatred, often associated with attacks on those who are Black, Jewish, and Catholic, was also aimed toward the Japanese.

It is in this context then that the raising of the “Japanese question” evokes chilling thoughts of the “Jewish question” that arose in Europe ahead of the horrors of the Holocaust. In 1921, House Joint Resolution 6 was overwhelmingly passed. It proposed a conference with legislators from Washington and Idaho to examine the Japanese question, to explore a counter to the “aliens” who may “become a serious adverse factor in the progress of our people …” In the same year, the Oregon House passed a bill prohibiting immigrants ineligible for citizenship, such as the Japanese, from owning or even leasing land. It failed to advance after Senator W.W. Banks motioned to postpone it in the Senate. He would be defeated by a primary challenger the following year. The KKK saw its power achieve new heights with the victory of Governor Walter Pierce in 1922. Pierce, who would also serve as a U.S. Representative of Oregon in Congress, was among the most vocal and vitriolic bigots against the Japanese not just in Oregon but the country at large.

Pierce’s election to Governor of Oregon preceded a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 1922 that emboldened the anti-Japanese movement. In Takao Ozawa v. United States, the court ruled that Issei were ineligible for citizenship because they were not white. The Oregonian, which had previously advocated for Japanese naturalization within the state, fell in line with the ruling and abandoned the cause. In 1923, three onerous laws aimed at the Japanese residents of Oregon would pass.

The Oregon Alien Land Law banned immigrants deemed ineligible for citizenship from owning land. The Oregon Alien Business Restriction Law allowed municipal governments to refuse business licenses to immigrants and required any existing stores owned by those born abroad to display signs indicating their nationality. Finally, House Bill 120 directed counties to compile lists of Japanese and Chinese residents who owned or leased land within their boundaries. These stateside assailments would be joined by federal legislation when the U.S. Immigration Act of 1924 passed and drastically reduced the number of immigrants allowed in each year and made it nearly impossible for those from Asia to arrive on American shores. Oregon would see a 30% drop in its Japanese population from 1924 to 1928.

In 1925, one of the ugliest anti-Japanese incidents in the state occurred in the small lumber town of Toledo when a mob of 75 white people stormed the housing of Japanese individuals under the employ of the Pacific Spruce Corporation. 35 Japanese people, workers and their families, were intimidated, threatened, and forcibly evicted from their company housing before being thrust on trains to Portland carrying whatever possessions they could in hand. Later five victims would win a landmark court case after they sued Toledo residents who had participated in this attack.

Statewide bans prevented Oregon’s Issei from purchasing land, but many managed to circumvent the law through their American-born children. Masuo Yasui, who as far back as 1917 had suggested an alien land law would be ineffective, would demonstrate how to skate by it by recording deeds in the names of his sons Kay and Tsuyoshi. Other Issei would have land purchased on their behalf by friendly white neighbors. The Japanese community of Hood River thrived as agriculturalists, dominating production of produce such as asparagus and strawberries until the 1940s. By 1941, Japanese farmers produced nearly all of the state’s cauliflower and broccoli, three-quarters of its celery, and well over half of its green peas.

There were white Oregonians who accepted their Japanese neighbors with compassion and friendship. In an interview conducted in 2003 by Jane Comerford for the Densho Digital Repository*, former Portland Japanese Garden Board of Trustees President Sam Naito (Nisei) recalled living in relative peace during his youth. “…No one objected to my father and mother moving into [a house on] Fifty-eighth and Burnside [in Portland],” he shared. “The neighbors were all very friendly, very accepting. Next door was a Norwegian couple named Olsen. And next door to that was Marlow, who was a fireman, and he was very friendly, and on the corner was Ward … and everybody was very friendly.”

Sadly, the kindness that Naito and others experienced was always against a larger backdrop of government-empowered hostility. It would reach a fever pitch in the 1940s.

1941-1945: The Domestic Tragedies of World War II

On December 7, 1941 the Japanese military conducted its surprise attack on the U.S. Naval base at Pearl Harbor. Though this was conducted by a foreign military, those of Japanese descent, a community had lived in the United States now for more than a generation, became the undeserving targets of governmental persecution. Before the wholesale arrest of innocent residents and citizens and establishment of American concentration camps throughout the West, the FBI abducted dozens of Issei living in Oregon–civic leaders, reverends, entrepreneurs, and other normal and innocent individuals to whom no guilt should have been attributed.

Oak Grove native Sab Akiyama (Nisei) told Linda Tamura for Densho in 2013, “[FBI agents] walked in and we thought we heard something coming upstairs, that’s where our bedrooms were, you know, the folks and us. Then we all woke up when this one fellow’s standing right by the door, and the other fellow was telling Dad to get dressed and come downstairs, and we tried to get up and this fellow said, ‘You guys just stay there.’ And he stayed there all the time while Mom went downstairs with Dad, and we went through the desks where Mom had kept letters she got from home. And that’s what really disturbed her, is she said they took all her letters.”

“… Of course, they took Dad, too … For a while, we didn’t even know where Dad was, ’til after, about the end of December, [we] got a message through [the] grapevine or something, that Dad wanted a shaving kit and stuff to shave…He was in Multnomah County Jail.”

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order No. 9066, in which he authorized the government to declare areas from which people could be excluded. Though the document never mentioned Japanese immigrants nor Japanese Americans, it was wielded against them and led to their mandated removal from western Oregon and points north and south along the American Pacific coast. It so happened that on the same day, Portland’s city government committed its own needless act of bigotry when it passed a resolution calling for the removal of those of Japanese ancestry during the war. This followed just a few months after they had banned business licenses for Issei members of the community.

As this onslaught on their liberty and freedom occurred, a young Oregonian made a stand that would burnish his legacy as one of the great civil rights heroes in American history. On March 28, 1942, 26-year-old Minoru Yasui walked the streets of Portland past a military curfew that was issued after Roosevelt’s executive order and before Portland’s Japanese population was incarcerated. Among the first of Oregon’s Nisei to graduate from the University of Oregon School of Law and the first to become a member of the Oregon bar, Yasui acted with no naivety and knew full well he’d be arrested and charged. His attorney would argue that by virtue of the 5th and 14th Amendments of the U.S. Constitution, his civil rights had been violated as an American citizen. Judge Alger Fee would nonetheless say that Yasui’s previous work for the Japanese Consulate had rendered him an enemy alien and thus subject to the curfew. He was sentenced to one year. Yasui would spend nine months in solitary confinement as he appealed his case.

In 1943, the Supreme Court would rule that Yasui had not forfeited his American citizenship but coupled that with an atrocity when it said his rights could be overridden based on his race in a time of war; that by virtue of being of Japanese ancestry, he would be more likely to betray the nation he had been born, raised, and educated in. After spending time in Minidoka Relocation Center in Idaho, Yasui returned to his civil rights work as a lawyer. In 2015, he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama, the first Oregonian to receive the honor.

As Yasui suffered imprisonment, the American government proceeded with one of its bleakest and most disheartening assaults on a marginalized community when Lieutenant John L. DeWitt issued Exclusion Order No. 26, a demand that those of Japanese ancestry in Multnomah County report to the Portland Assembly Center (now the Expo Center) by May 5, 1942. The center, which had held livestock, was transformed into a ramshackle prison for the 3,500 who arrived. This was a place where even basic decency to expecting mothers was in short supply. Emi Somekawa (Nisei) told Tom Ikeda for Densho in 2011 about going into labor while at the assembly center. “[A doctor] said that, ‘Emi is pregnant and I’m gonna have to deliver her because she had such a difficult delivery,’” Somekawa recalled. “I can’t even remember what his title was, but anyway, he was the executive director of the assembly center anyway, and he said, ‘Sure. The minute her labor starts call me.’ I did, and the ambulance was there and took me to Emanuel Hospital, delivered me that night. And next day the ambulance came back to pick me up, bring you back to the base hospital ’cause they didn’t want me away from the assembly center any longer than I had to be.”

After a few months, these families would be sent to American concentration camps such as Minidoka or Tule Lake War Relocation Centers. Many would not come back to the region.

“I think it’s … the most traumatic thing is the fact that I had to leave Portland one month before I was to graduate high school,” Portland native Chiye Tomihoro (Nisei) told Becky Fukuda in a 1997 interview for Densho. “And that was really very, very sad, especially since we were only ten miles away, at the Portland Assembly Center, from my school. I’d think, ‘Why couldn’t they just let me go to my graduation?’”

The eviction and incarceration of people like Somekawa and Tomihoro would not be enough for too many of the people they left behind. Oregon State Senator Thomas Mahoney of Portland would push a memorial that would petition Congress to prevent Japanese Americans from serving in the military and canceling the citizenship of all Japanese Americans. He would be met by resistance from groups that would be among the more consistent advocates for the rights of Oregon’s Nikkei: the Portland Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), Portland Council of Churches, Oregon Christian Youth Council, Oregon Council of Church Women, and Portland Chapter of Women’s International League for Peace Freedom. The Minidoka Irrigator, a newspaper created by incarcerees at the Minidoka Relocation Center, quoted the Women’s International League pushing back at Mahoney, noting “this group (Japanese) has been truly American in that it has followed the good American custom of hard work, thrift, purchase of land and education of youth.”

In the first half of the 1940s, these organizations were protesting others that had greater influence and more resources than them. The Portland Chamber of Commerce, no longer concerned about how the treatment of Japanese Americans would affect a bottom line, advocated for their permanent banishment. Gresham Mayor Ralph Hannan would co-found Oregon Anti-Japanese Incorporated, a group that sought to amend the state’s constitution to achieve the same goal as the Portland Chamber of Commerce: engineering the temporary expulsion of the area’s Nikkei into a permanent one.

Words on paper would not be enough for those with violent impulses. In the summer of 1943, the Rose City Japanese Cemetery would be desecrated. Approximately half of its 500 grave markers were either vandalized or outright destroyed and the landscape was set aflame. When the Portland Fellowship of Reconciliation attempted to restore the cemetery, they were blocked by members of the American Legion, Multnomah County Sheriff Martin Pratt, and the county’s District Attorney, James Bain. Despite the fact the deceased had no part to play in the war, the leader of the Portland Elks Lodge, Lew Wallace, claimed that tending to the cemetery would be “an insult to the American war dead.”

After too many years of conflict, too many lives lost, and too many homes wrought into ruin, Japanese Emperor Hirohito delivered a radio address in which he accepted the terms of the Potsdam Declaration, marking Japan’s surrender on August 15, 1945. Weeks later, on September 2, U.S. General Douglas MacArthur accepted the surrender and World War II ended. The hardship and cruelty the Japanese American community of Oregon faced would not.

1945-1960: The Return to Oregon

A little more than two-thirds of the Japanese and Japanese American Oregonians incarcerated during the war would return to the place they considered home. Some, however, felt the bigotry in Oregon would be too great to handle. Diana Morita Cole (Nisei) was incarcerated at birth as she was born in Minidoka War Relocation Center in Idaho in 1944. “I was about a year and a half when we moved to Chicago,” she told Virginia Yamada for Densho in 2019. “We were one of the last to leave, and I remember my sister, Betty, telling me that she was really upset because everybody had gone and they were practically the last ones to leave, but my father was holding out with the notion that he might return to Oregon. But none of my brothers and sisters wanted to go back because there were these headlines that said, ‘J*** not wanted here,’ it was very, very racist. And so he realized that if he wanted to stay with the family, he would have to go to Chicago … He never liked the jobs he had there, he always talked about Hood River and how beautiful it was, so I think there was this great longing for it in his life.”

Some Issei and Nisei, soured on the American experience, decided to repatriate to Japan. In December of 1945, large ships departed Portland for the archipelago nation, ferrying passengers who felt they’d stand a better chance even in a place devastated by war.

Those who did return to Oregon found that bigotry was still an insidious presence in the state. Portland’s Japantown was now gone, leaving returning Nikkei without the comfort of a cultural enclave to reestablish the lives they had once known. “There was still a lot of discrimination,” Fumi Kaseguma (Nisei) told Tom Ikeda for Densho in 2007. “People had a hard time getting apartments.” Kaseguma and many other families of Japanese descent, roadblocked by the racist real estate practices that also marginalized Black Oregonians, would wind up living in Vanport, a massive wartime housing development on lowlands near the Columbia River, today the site of the Portland International Raceway and Heron Lakes Golf Club.

Engineered in such a way that made it prone to flooding, disaster struck on May 30, 1948, when the Columbia River, roaring from weeks of pouring rain, breached embankments. The fact that it was Memorial Day and many were away turned out to be the reason why the death toll (15) was not significantly higher. On the same day of the flood, the Housing Authority of Portland (HAP) had distributed a flyer to residents assuring them that the dikes were safe and that they would provide notice if evacuation was necessary, all while making sure to clear out files, equipment, and horses from a nearby racetrack. The dikes would not be safe and when they failed, 18,500 individuals would only have a little over half an hour to escape. Almost of all of Vanport’s 1,000 Nikkei residents survived—some because they had been attending an event at the Rose City Japanese Cemetery, others because years of mistreatment by governmental bodies had fostered enough distrust that they duly ignored the messaging from the HAP and evacuated before the flood. It was a devastating experience for so many who had only just a few years prior experienced the trauma of incarceration.

Hood River, where a Japanese American community had thrived before World War II would see such individuals return, but to an all-too hostile climate. Before the war had concluded, the Hood River American Legion took down plaques honoring 16 Nisei soldiers from the American military because they questioned their loyalty. The incident would spark national outrage, but the eventual restoration of the plaques did little to end the racism there. Linda Tamura, Professor Emerita of Education for Willamette University (Sansei, or third generation Japanese American), writes about reading old newspapers from the region she was raised in:

“There were notices discouraging Japanese Americans from returning home after the war. The 1945 headline from one of several full-page ads attested: ‘J*** Are Not Wanted in Hood River.’ Even more unsettling was the list underneath of hundreds of residents who had signed the appeal. I recognized names of neighbors, family members of my classmates, even a former teacher.”

Of course, there were those in Oregon who welcomed back the returning Nikkei with open arms. Reflecting on her time attending Roosevelt High School in Portland after WWII, Setsu Tsuboi Tanemura (Nisei) told Densho contributor Tom Ikeda in 2009, “All the kids in that class were very protective … I don’t know why, but someone was always looking out for me.”

Prior to arrest of its Japanese and Japanese American population, support for these individuals and families was often inconsistent or feckless. Sometimes defense was only borne out of fidelity to money. Rare was the individual who spoke to universal and moral truths. Only one white person, Azalia Emma Peet, spoke against it in ethical terms in Portland during the Tolan Committee hearings in 1942, a series of public discussions regarding plans for concentration camps. As Oregon’s Nikkei were expelled to their concentration camps, more people found nerve and a resilient effort to bring them back grew.

Former Oregon Governor Charles Sprague and Gus Solomon, a prominent Jewish activist who would go on to become Oregon’s longest serving federal judge, were among those who found nerve where it had previously failed them and became two of the most outspoken advocates for their neighbors. Solomon would face death threats in the face of his vocal defense. These individuals and organizations such as the Portland Council of Churches and YWCA would publicly and loudly push back against anti-Japanese editorials and governmental bills. When the war ended, the War Relocation Authority (WRA), once tasked with removing Nikkei from places such as Oregon’s West Coast, shifted into an agency responsible for their resettlement. Oregon-based WRA officials such as Henry Fistere and Clyde Linnville would also publicly and consistently push back against anti-Japanese sentiment, while leading an organized movement to find permanent shelter and gainful employment for the returning Issei and Nisei.

These individuals and organizations were important, but none more essential to the return of those of Japanese ancestry than those of Japanese ancestry. The Community Affairs Committee, made of Issei and Nisei and working out of the Nichiren Buddhist Church, were a prominent organization in the community that not only helped provide aid to those who returned, but also were stalwarts in the fight to remove and repeal anti-Japanese laws and regulations.

Other critical figures in the battle to shed Oregon of its racist laws were Etsuo and Kenji Namba, a father-and-son duo who sought to lease land for a 62-acre farm. In 1945, the Oregon State Legislature had passed a new Alien Land Law, an update to the 1923 iteration, but this time closing loopholes that allowed Issei to put ownership or leasing of land under a wife or child’s name. The Nambas sought circuit court approval to move forward with the lease, an agreement that was a direct violation of the racist law. When they were denied, the Nambas successfully appealed the case to the Oregon Supreme Court in 1949, which ruled that the Alien Land Law violated the state constitution.

Some individuals even joined organizations that had mistreated those of Japanese ancestry, so they could create change from within. The Clackamas County-raised Joe Saito (Nisei) told Alton Chung for Densho in 2004 how the racist actions of the Hood River American Legion inspired him to act. “During the war I’d heard about this, the Hood River Post of the American Legion had removed the names of Nisei on [the roll of honor]…,” Saito, a WWII veteran, shared. “And things like that made me determined, I was gonna try to join the American Legion when I came home. …There’s no use trying to fight from the outside if you can get in on the inside, so when I came home that’s the first body I asked if I could join. … I was one of the early World War II veterans in our post, and I was welcomed into the post here. Wherever I had an opportunity to keep things like that from happening, it never happened again. The Hood River Post has entirely changed. In fact, the Hood River American Legion Club was run by a Nisei for many years.”

With Japantown largely gone, devastated by the forced evacuation of its residents and business owners, those of Japanese ancestry moved into locations throughout Portland. “It was not the thriving growing Japantown prewar prior to World War II,” Portland born George Nakata (Nisei) told Denshointerviewer Masako Hinatsu in 2004. “And so the Nikkei community started to spread out, grocery stores in North Portland, in Milwaukie and insurance businesses, insurance agents. And in a way, it was really the beginning of what there is today when there are outstanding cardiologists, outstanding educators, outstanding business professionals, lawyers. People that are on every walk of commercial life in the Portland Metro area, you will find in the Nikkei community. It was not like that during the early years. But during the 1950s and ’60s, you can see this emerging. And so they spread their wings and new businesses started to pop up.”

Even after the region had seen most of the worst kinds of hatred tempered and minimized, anti-Japanese sentiment still existed well into the 1950s. “When we first got married and moved into this four-plex, the gentleman who was renting us the room — this is in 1957 — he said he had to ask the neighbors if it was all right for us, being Japanese, to move into the apartment complex,” Portland native Alice Matsumoto Ando (Nisei) told Denshointerviewer Betty Jean Harry in 2014. “And I thought that was rather odd. This was so many years after the war, and there was still some feeling of prejudice. And I didn’t quite understand that. It kind of boggled my mind. I thought, my goodness, all these years have gone by, and there are still some people who have feelings of prejudice.”

While discrimination was still all too present in Oregon, there were signs of progress in the treatment of the state’s Nikkei in the 1950s. In 1952, just a decade after Portland’s government had espoused support for the incarceration of its innocent residents, Mayor Dorothy McCullough Lee and Portland Chamber of Commerce President Edgar Smith accepted a gift of 2,000 cherry tree seeds from Consul Masayuki Harigai. In this decade, Oregonian Issei were able to finally naturalize as citizens and were congratulated by staff of The Oregonian not so long after paper had published its demagoguery against them. In 1960, Oregon Governor Mark Hatfield received Crown Prince Akihito. Portland in particular would see an idea grow momentum and support: the establishment of an authentic Japanese friendship garden.

1963-Today: The Path for Cultural Understanding

As early as 1954, when Portland received the gift of a stone lantern (known today as our Peace Lantern) from the City of Yokohama and its mayor, Ryozo Hiranuma, there were reports of parties, white and Asian alike, interested in building a Japanese garden. The 1959 establishment of a sister-city relationship between Portland and Sapporo would become a major catalyst for the creation of Portland Japanese Garden. What began as a grassroots push from local Japanese cultural organizations and other civic leaders became an effort quickly championed by a government constituted of people who understood the value of cultural understanding.

It was determined the site the old, abandoned Portland Zoo in the city’s Washington Park should become an authentic Japanese landscape. Oregon Governor Mark O. Hatfield and Portland Mayor Terry D. Schrunk co-wrote in a 1960s communique, “Not only will [a Japanese garden] enhance the tourist appeal of [Portland], but it will serve to strengthen the close bonds that already exist between our peoples.”

As Portland Japanese Garden was established in 1963, it retained Professor Takuma Tono of Tokyo Agricultural University to design its grounds. A proponent of cultural diplomacy and an educator, Tono promoted the idea that the Garden could be a living museum and planned four (later five) distinct styles that would offer examples of landscapes representative of eras throughout Japanese history. Portland Japanese Garden opened to the public in 1967 and in its first year saw 28,000 visitors. Programming was added in subsequent years, including exhibitions of Japanese horticultural arts like bonsai, traditional festival celebrations, and shows of classic and contemporary Japanese art. Portland and its tourists enthusiastically responded to these offerings—a city that had deprived its Nikkei neighbors of their personhood was now expressing deep interest and pride in its immaculate Japanese garden and the events it held.

Through these offerings, the organization espoused a subtle way of presenting and explaining a foreign nation’s people and customs—experiences of art, nature, and peace that allowed space for empathy and understanding of the “other.” Importantly, it went further than giving a platform to the gifts of just one culture—it demonstrated to those hailing from other continents and hemispheres that they need not hide the values and practices they took with them to American shores. Luba Gonina, a licensed clinician with Lutheran Community Services and immigrant from the former Soviet Union, shares, “I have shared the Garden with clients from Russia, Eastern Europe, Burma, Nepal, Syria, and Iraq. When they visit the Garden, they see a story of commitment to successful cultural integration. And this is inspirational. It shows them they don’t have to ‘blend in’ to integrate into American society. They can, in fact, contribute their ethnic tradition to their communities.”

Today, Portland Japanese Garden welcomes over 400,000 guests annually from every state within the U.S. and more than 90 countries. It also has become a nexus through which several Japanese organizations, governments, and businesses intersect. As Oregon became home to 130 Japanese companies and over 27 sister-city relationships, the Garden became a tentpole of a robust regional network of organizations promoting Japanese cultural heritage.

But work still remains.

Even with a thriving network of Japanese and Japanese American organizations and businesses, Portland, Oregon – a city of over 630,000 residents – is considered one of the least diverse major American cities, with more than 73% of its population identifying as white per the U.S. Census. The state’s fraught history of exclusionary laws and regulations targeted at ethnic minorities impacts its makeup to this day. Contemporarily, Asian Americans in Oregon have reported an uptick in the number of instances they have personally experienced bigotry and hate crimes. Japanese and Japanese American people both living in and visiting Oregon have been victims of racist assaults in recent years.

However, one needs to look back only a few generations back to see how far we’ve come and to know the resilience of Oregon’s Nikkei and their allies will, with Portland Japanese Garden’s help, continue to dismantle bigotry and hatred. The Garden has gone a long way to attenuating hostility toward those of Japanese descent. Vice President of the organization’s Board of Trustees and retired neurosurgeon, Dr. Calvin Tanabe, is a Portland native. He was incarcerated at the Minidoka War Relocation Center from 1942 to 1945. “I think every Japanese American person who lived through [World War II] was not very well appreciated,” Tanabe (Nisei/Sansei) has shared. “Things are a lot better [now]…the Garden has gone a long way to creating these better feelings.”

In just 60 years, Portland Japanese Garden has demonstrated how a public space meant to connect people to nature, culture, and each other can help transform society. As a community-driven organization, Portland Japanese Garden will continue to bridge divides that need never have existed in the first place so that more people in more places may one day experience a future where all can feel inspiration through harmony and peace.

Written by Will Lerner, Communications Manager, Portland Japanese Garden & Japan Institute.

References

Azuma, E. (1993). A history of Oregon’s Issei, 1880-1952. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 94(4), 315-367. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20614543

Chung, A. [Japanese American Museum of Oregon]. (2004, December 3). Joe Saito interview [transcript]. Densho Digital Repository. https://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-one-7-36-1/

Comerford, J. [Japanese American Museum of Oregon]. (2003, January 15). Sam Naito interview [transcript]. Densho Digital Repository. https://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-one-7-1-1/

Cox, T. (2005). The Toledo incident of 1925. Old World Publications.

Diamond, A. (2020, May 19). The 1924 law that slammed the door on immigrants and the politicians who pushed it back open. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/1924-law-slammed-door-immigrants-and-politicians-who-pushed-it-back-open-180974910/

Eisenberg, E. (2003). “As truly American as your son”: Voicing opposition to internment in three West Coast cities. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 104(4), 542-565. https://doi.org/10.1353/ohq.2003.0012

Foss, C. (2017). “I wanted Oregon to have something”: Governor Victor G. Atiyeh and Oregon-Japan relations. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 118(3), 338-365. https://doi.org/10.5403/oregonhistq.118.3.0338

Fukuda, B. [Densho]. (1997, September 11). Chiye Tomhiro interview [transcript]. Densho Digital Repository. https://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-densho-1000-93-1/

Harry, B.J. [Japanese American Museum of Oregon]. (2014, June 13). Alice Matsumoto Ando interview [transcript]. Densho Digital Repository. https://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-one-7-73-1/

Hegwood, R.A. (2011). Erasing the space between Japanese and American: Progressivism, nationalism, and Japanese American resettlement in Portland, Oregon, 1945-1948. Dissertations and Theses, Portland State University. Paper 151. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.151

Hinatsu, M. [Japanese American Museum of Oregon]. (2004, August 23). George Nakata interview [transcript]. Densho Digital Repository. https://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-one-7-29-1/

Ikeda, T. [Densho]. (2007, November 6). Fumi Kaseguma interview [transcript]. Densho Digital Repository. https://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-densho-1000-203-1/

Ikeda, T. [Densho]. (2009, November 12). Setsu Tsuboi Tanemura interview [transcript]. Densho Digital Repository. https://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-densho-1000-266-1/

Ikeda, T. [Densho]. (2011, November 21). Emi Somekawa interview [transcript]. Densho Digital Repository. https://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-densho-1000-378-1/

Jessie, A.L. (2015). Questions of citizenship: Oregonian reactions to Japanese immigrants’ quest for naturalization rights in the United States, 1894-1952. Portland State University Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2644. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2640

Johnson, D. P. (1996). Anti-Japanese legislation in Oregon, 1917-1923. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 97(2), 176-210.

Kakishita, J. [Japanese American Museum of Oregon]. (2013, November 30). Albert A. Oyama interview [transcript]. Densho Digital Repository. https://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-one-7-52-1/

Keddie, G. (2013). Japanese shipwrecks in British Columbia. Royal British Columbia Museum. https://staff.royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/JapaneseShipwrecks-Grant-Keddie.pdf

Kitagari, G. (2023, June 30). Japanese Americans in Oregon. Oregon Encyclopedia. https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/japanese_americans_in_oregon_immigrants_from_the_west/

The Minidoka Irrigator. (1943, March 20). Defeat of memorials church aim. https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-119/ddr-densho-119-32-mezzanine-cd3181b4d8.pdf

Nagae, P. (2012). Asian women: Immigration and citizenship in Oregon. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 113(3), 334-359. https://doi.org/10.1353/ohq.2012.0063

National Park Service. (n.d.). Castaways from Japan at Fort Vancouver. https://www.nps.gov/articles/castawaysatfova.htm

Office of the Historian. (n.d.). The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (the McCarran-Walter Act). United States Department of State. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/immigration-act#:~:text=the%20full%20notice.-,The%20Immigration%20and%20Nationality%20Act%20of%201952%20(The%20McCarran%2DWalter,controversial%20system%20of%20immigrant%20selection

Ozawa v. United States. (n.d.). Densho Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Ozawa_v._United_States/#:~:text=Ozawa%20was%20born%20in%20Kanagawa,to%20Honolulu%20and%20settled%20down.

Tamura, L. (1993). Railroads, stumps, and sawmills: Japanese settlers of the hood river valley. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 94(4), 368-398.

Tamura, L. [Japanese American Museum of Oregon]. (2013, October 30). Sab Akiyama interview segment 1 [transcript]. Densho Digital Repository. https://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-one-7-48-1/

Tamura, L., & Matthews, M. T. (2013). What would you do? If heroes were not welcome home. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 114(2), 226-229. https://doi.org/10.5403/oregonhistq.114.2.0226

Yamada, V. [Densho]. (2019, September 30). Diana Morita Cole interview [transcript]. Densho Digital Repository. https://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-densho-1000-483-1/

Zell, J. & Feldman, M. (1976, February 14). Gus Solomon interview. Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education. https://www.ojmche.org/oral-history-people/gus-solomon/

*Densho, a nonprofit organization based in Seattle, has spent more than 25 years working with cultural organizations such as the Japanese American Museum of Oregon in collecting archival materials and conducting interviews with Japanese and Japanese American individuals (and others connected to these communities) about their experiences in the U.S. for the Densho Digital Repository. We are indebted to them for their work, which allows us to incorporate and elevate the voices of Oregon’s Nikkei population in this article.