While Portland Japanese Garden’s 12.5 acres are confined to its home city, it manages to transcend its physical boundaries and transport visitors across an ocean to Japan. Amazingly, it does this despite being enveloped by an unmistakably Pacific Northwest forest and featuring elements that have never known a home other than Oregon. Unlike many Japanese gardens around the world that depict one style, the unique collection of five different styles at Portland Japanese Garden required early Garden leaders to motor to locations near and far across the Beaver State to find the right materials. While their collection of many materials, such as stones, from wild areas in Oregon is no longer allowed today, it was permissible in the 1960s. Interviews conducted by former Portland Japanese Garden Board of Trustees President Ed McVicker (2009-11) help illustrate their efforts.

Columbia River Gorge

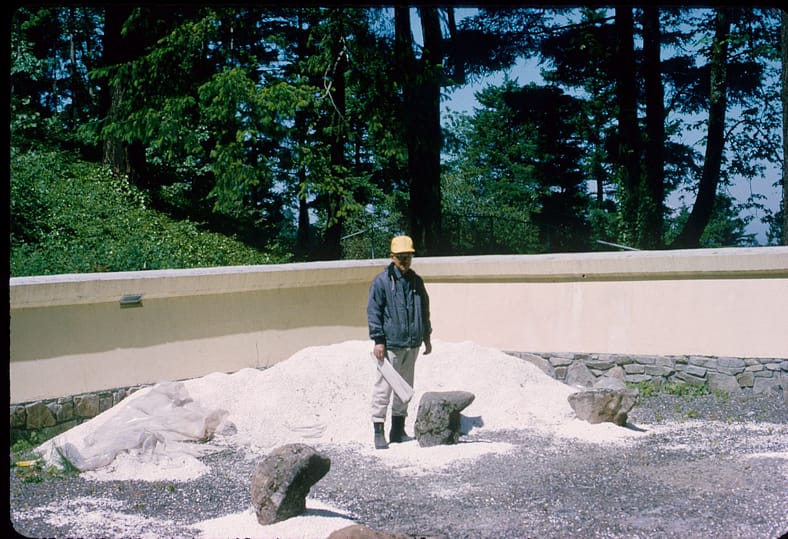

The Sand and Stone Garden features stones in an arrangement that has often been interpreted as a depiction of the story of Buddha (the tall stone) sacrificing himself to feed starving tiger cubs (the seven smaller stones). William “Robbie” Robinson, former Head Gardener of Portland’s Parks and Recreation Bureau, and one of the most important contributors to the Garden’s construction, told McVicker that the efforts to source the tall “Buddha stone” almost went awry.

“I took [the Garden’s original designer, Professor Takuma Tono] up to right around Starvation Creek Park,” Robinson shared, referring to a natural area adjacent to Interstate 84. “There’s a whole mountain that has a wall built to keep the mountain from coming down. There were a few options up there, way up on the loose gravel. One of my sons-in-law went up there and got the Buddha stone started down the hill. All the shell rock that was up there started to come down too. I thought, ‘Oh my god, if this doesn’t stop coming down, it will plug up the highway and Columbia River Gorge. The rocks kept coming down and finally stopped within two feet of the road. We almost had a big disaster.”

Other stones in this garden space were procured in manners far less dramatic. Robinson shared that the stones that serve as a foundation for the garden’s stucco walls are from the Historic Columbia River Highway. The tiger cubs, meanwhile, were taken from areas off the Wapanitia Pass.

City of Portland

The Flat Garden features Portland Japanese Garden’s only weeping cherry – a dictate from Professor Tono who felt its blooms were so dramatic that more than one would have been too much. This stunning tree is from a nearby neighborhood in Portland. Once belonging to local resident Dr. George Marumoto and his family, the weeping cherry was rescued from a street targeted for expansion. Now nearly 80 years in age and nearly fifteen feet in height, it radiates in hues of bright pink and is a reliable bellwether of spring.

Expressing a more muted grandeur than the weeping cherry are long, white slabs of granite seen throughout the Garden. These are sourced from the 1966 renovation of the Portland Civic Auditorium, now known as the Keller Auditorium. The Oregonian reported at the time that after a “quiet preservation ceremony,” the granite slabs, previously used as stairs into the theater, were lifted gently out of place and lowered into a truck bound for the Garden. They can be seen today in several areas, including the Eastern side of the Pavilion.

Other stones from the greater Portland area were also repurposed within the Garden, including those placed in front of the Sapporo Pagoda Lantern in the Strolling Pond Garden. Originally from Dodge Park, an area east of Portland along the Sandy and Bull Run Rivers, these stones are arranged to represent the Japanese island of Hokkaido, a prefecture with the capital city of Sapporo, Portland’s sister city. The sole reddish-hued stone in this tableau was sourced from Terrebonne, Oregon, a stretch of land about 30 minutes north of Bend.

Mt. Hood

The Garden features so many stones taken from Mt. Hood that former Garden Director Hoichi Kurisu (1968-73) joked, “Even now on a clear day we can see Mt. Hood from [the East Veranda] and there’s a little section that is missing. That’s because the Japanese Garden took it all.”

“Most of the river stones came from Mt. Hood,” former Garden Director Masayuki Mizuno (1977-80) shared. “We harvested them in rivers or former rivers, where the water had polished the stones for thousands of years. We were lucky that we were issued a permit from the state to harvest them.” Some stones, however, were not as willing to come back to the Garden.

“They were very fun trips to gather river stones, but there was an incident when we were trying to cable a large boulder,” Mizuno recalled. “[Former Head Gardener] Michael Kondo and I strapped the cable around it, thinking that it was enough. When the big crane truck started to pull the boulder up, the wire was not tight enough and the boulder came loose. It came falling really fast, and fell right in between Michael and me. We were in awe.”