Musings by Diane Durston, Curator Emerita

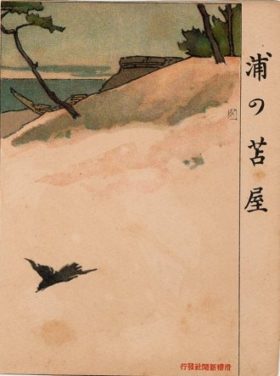

見渡せば / 花も紅葉も / なかりけり / 浦の苫屋の / 秋の夕暮れ

Miwataseba / hana mo momiji mo / nakarikeri / ura no tomaya no / aki no yuugure

Casting wide my gaze,

Neither flowers

Nor scarlet maple leaves–

A humble fisherman’s hut,

In the autumn dusk.

With this poem, Fujiwara no Teika, an aristocrat of the 13th century and one of Japan’s greatest poets, offers a glimpse of that elusive sense of quiet beauty that centuries later would come to be known as wabi-sabi (侘寂).

In Teika’s world, the word wabishii described the emotions a poet might feel when coming upon a poor fisherman alone in his humble hut beside the sea. Sabishii referred to things old and withered—an object or an experience that moved a poet to feel the universal sense of the loneliness of someone contemplating his own mortality.

In Teika’s world, the word wabishii described the emotions a poet might feel when coming upon a poor fisherman alone in his humble hut beside the sea. Sabishii referred to things old and withered—an object or an experience that moved a poet to feel the universal sense of the loneliness of someone contemplating his own mortality.

The combined notion of wabi-sabi (侘寂) evolved from these poetic beginnings to inform the heart of the tea ceremony, a disciplined practice in which guests meet their host in a rustic tearoom to brew and enjoy a simple cup of tea, connecting quietly in this setting with nature and each other. The goal is to understand the value of slowing down to experience each moment as it passes, taking one thing at a time, and appreciating the calming effect of order and cleanliness.

Defining wabi-sabi in any language is not easy. The very character of Japanese language and culture resists analytical dissection and embraces the freedom of open-ended ambiguity. Wabi-sabi is a compound of two words, each with a long history of evolving meanings over time.

To everyone struggling with the chaos of life in these uncertain times, wabi-sabi asks us to understand the value of slowing down to experience each moment as it passes

Wabi (侘) has been called poverty enlightened. Herman Hesse said that the wisest thing a starving man can do is fast. Zen monks are not poor people; they have chosen a stripped down and lean existence believing that therein lies a path to the truth. Such a life serves as a metaphor for the beauty of a modest, humble human heart

Sabi (寂) is an appreciation for life as it is — full of both dark and light, beauty and ugliness, sorrow and joy. It is an appreciation for objects that show the effects of the passage of time, but it goes beyond an aesthetic ideal. True beauty lies in an appreciation for the many hands that have touched it—the hands of the humble potter who made a tea bowl, the hands of guests at a tea ceremony that have passed a rustic bowl from one person to the next, sharing it among friends perhaps for generations. It can be felt in the care with which that bowl has been handled, sometimes even broken and painstakingly repaired.

Collection of the Ethnological Museum of Berlin

To everyone struggling with the chaos of life in these uncertain times, wabi-sabi asks us to understand the value of slowing down to experience each moment as it passes, taking one thing at a time, and appreciating the calming effect of order and cleanliness.

Loneliness and poverty seem always to be with us. Finding beauty in this world of broken dreams is as important now as it was in the 13th century. Perhaps compassion is at the heart of wabi-sabi. Or perhaps it is for each of us to define in the 21st century for ourselves. Learning to live in a conscientious and appreciative way may be meaning enough.

Diane is the author of Wabi Sabi: The Art of Everyday Life, a collection of quiet meditations on life lived simply and with intention, and three books on Kyoto (all available online).