The phrase “God is in the details” is, with uncertainty, attributed to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. But whether it came from the Modernist great or someone else, there is something about the play of detail in the creative process that transcends time and geography.

Detail occupies a particularly complex and nuanced role in the Japanese garden. The Japanese gardener’s planning process is embedded in the details – working up from the individual elements, rather than from a top-down master plan. A layout and sketches inform and help guide the process, but factors such as the available choice of materials can cause a change in the design. It can happen that the directionality of one particular boulder or composition of boulders, or the form of a single tree, becomes the focal point — and by that, the consideration that drives the design.

At the Portland Japanese Garden’s Training Center, we teach the techniques of the Japanese garden to landscape practitioners from outside Japan. Our method blends learning approaches both Eastern and Western, and we enrich lessons in traditional practices with cultural context and contemporary relevance. Studying the Japanese garden as an art form can lead to a deeper understanding of universal fundamentals of design such as balance, the use of empty space, and the impact of detail. It can help make connections across other forms and traditions, and the relationship of detail to the creative process. And it can make us see our own cultural forms anew, because some ideas that might seem deeply, entirely Japanese have resonant counterparts in Western culture:

Give focus to a detail by making space to hone in on a single essential point. The photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson ascribed the impact of a photographic image to the tiny details captured at just the decisive moment, saying that “it is by economy of means that one arrives at simplicity of expression.” Miles Davis echoed that sentiment a bit more tersely with: “I always listen to what I can leave out.” In a Japanese garden, the empty space around a design detail can give it greater impact and meaning. A tiny recessed decorative motif at the end of a clay plaster wall, a path laid out in all natural materials except for one repurposed piece of carved stone, or even an ephemeral detail like freshly-fallen bright-red maple leaves in a stone basin – all are made more striking by the negative space giving them room to breathe.

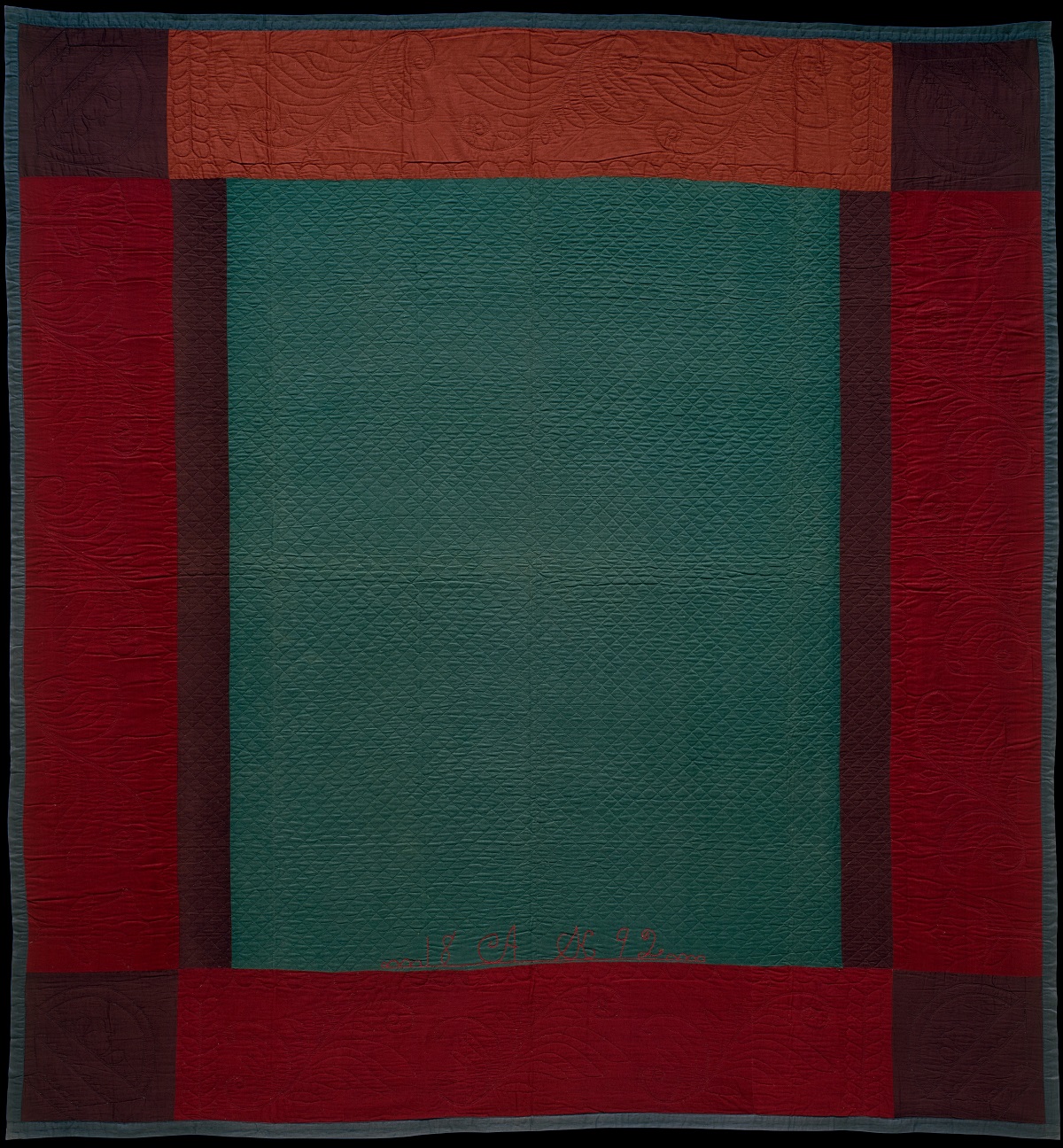

Limitations can inspire excellence in detail. Japanese garden expert, designer and author Marc P. Keane noted in his most recent book that “rather than design everything from the start, some parts of the garden will be created bit by bit as circumstances require with materials that happen to be on hand at the time. The result is a complex quilt that is impossible to achieve in any other way.” In other words, the garden’s design can unfold according to availability of just the right materials for the site, a result that might be quite different from what would result from following a master plan. The reference to quilts lends itself well. Early Amish quilt makers were restricted by religious and cultural custom to using cloth in modest, subdued shades of brown, blue, rust or black. They responded skillfully by creating patterns of up to 14 stitches per inch in intricate and flowing decorative designs inspired by the elements of the natural world that they loved. Swirling feathers, curves, and grids serve as a subtle representation of the resourcefulness and individual spirits of their makers — easily missed if one doesn’t know, or take the effort, to look for them. Flashy colors in striking patterns might be more eye-catching, just as a garden path of expensive and rare stone might loudly call attention to its owner’s power. But a garden path created of humble small stones – by, for example, the arare koboshi (fallen hailstones) style, involves selecting just the right river stones and fitting them together like a linear puzzle in just the right way. It speaks of a patron who expresses taste and wealth softly. The materials are humble, the artisan’s attention to detail is formidable, and the eye that recognizes the level of craftsmanship is rewarded.

A true master of detail takes care of the invisible, too. No one is sure why, but the Parthenon’s sculptural friezes included an immense amount of tiny sculptural details that, even with their original vivid colors, were, in their original siting, in some extremely hard-to-see places. In Japanese gardens, the finest details are sometimes in the most obscure places. Keane cites the sheaths of fine cypress shingles or thin plates of bark on a roof – well out of the sightline of a visitor on the ground – as an example of taking care with nearly-invisible details. So too are certain styles of bamboo fence, in which each node of each bamboo stalk has to be precisely cut with a notch to allow the neighboring bamboo piece’s node to fit. The technique itself is invisible to the viewer’s eye, which only sees a perfectly aligned and joined row of bamboo stalks. A work is only as good as its tiniest, least visible detail.

A well-chosen detail can be the most evocative voice. A gifted designer can include details in a garden from natural and manmade materials to suggest the place’s story, subtly depicting gentle human traces left on the landscape over time. Here at the Portland Japanese Garden’s Antique Gate, for example, repurposed roof shingles embedded in the ground in a seemingly random pattern around the gate suggest the passage of time that it took them to naturally fall from the roof and form scattered patterns on the ground. It also reflects the Japanese practice of mitate-mono, seeing an object anew. The same philosophy can be seen in the details of the High Line in New York, where Piet Oudolf paired native plants with hardscaping elements to quietly suggest the feeling of walking down a rail line abandoned by humans and gradually reclaimed by wild nature – right in the middle of the noise of 8.5 million people.

An entire history of a place can be fleetingly but powerfully referenced by a design detail. It’s a beautiful and sophisticated means of telling a landscape’s story.

Sometime after the phrase “God is in the details” was coined, its counterpart, “the devil is in the details” also became common currency. It’s common sense that failure to pay attention to small things can doom the large things in any project. But it’s far more captivating to believe that in paying devoted attention to detail, there is something that elevates us – and, by extension — the works that we make.

This post was written by former Japanese Garden Training Center Director, Kristin Faurest and was originally featured on landscape architecture blog, Land 8.

To contact the Japanese Garden Training Center, please email Sada Uchiyama.