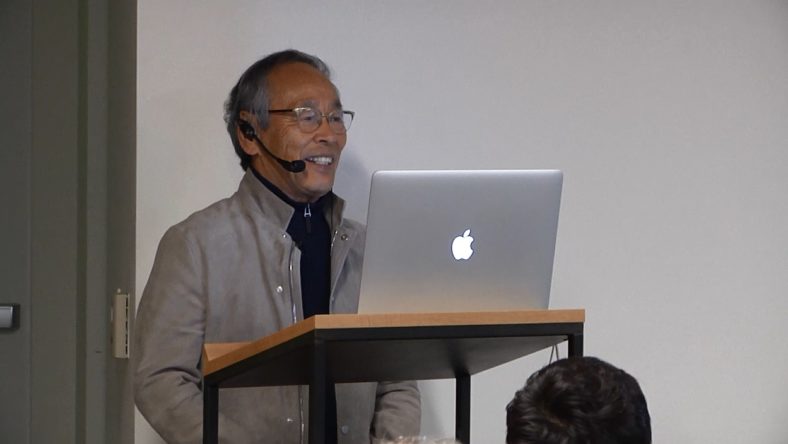

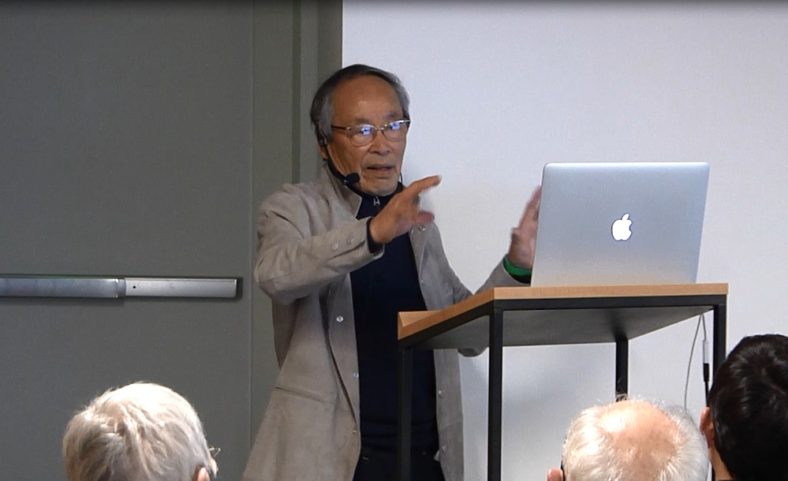

From deprivation comes inspiration. Of the many profound statements Hoichi Kurisu made during his February 15 lecture here at the Garden about the Japanese-inspired restorative landscape he is designing in cooperation with inmates and staff at the Oregon State Penitentiary, that may be the one that struck me most. There’s a certain clarity gained from having everything taken away.

Those who came to Kurisu’s lecture expecting a landscape design talk might have been surprised but surely not disappointed: it wasn’t about the design, but about how the garden project has galvanized inmates, staff, family, and community activists – several of whom accompanied him at the lecture — for a project that will be the first of its kind.

Those who came to Kurisu’s lecture expecting a landscape design talk might have been surprised but surely not disappointed: it wasn’t about the design, but about how the garden project has galvanized inmates, staff, family, and community activists – several of whom accompanied him at the lecture — for a project that will be the first of its kind.

The power of landscapes to heal human wounds is a phenomenon recognized for millennia, from the ancient Greeks’ temples of healing to the alpine tuberculosis clinics and beyond. But in recent times we’ve started to have a much broader understanding of what a landscape can restore to both body and spirit. We now see gardens created in unlikely places like homeless shelters, drug rehabilitation facilities, and of course, prisons. These are nothing other than an attempt to bring some sense of normalcy, health, stability, and positive energy to places sorely lacking in all those things.

University of Oregon professor emeritus Kenneth Helphand called them ‘defiant gardens’ in his book of the same name — in such unlikely places as the battlefields of World War I, Palestinian refugee camps, the Warsaw ghetto, internment camps, the civil war-torn streets of Bogota. They have many names and places, but they’re unified by one single idea: a garden isn’t a luxury. It’s a human essential and the ultimate embodiment of optimism and faith. It’s a belief in the future and a connection to home.

Creating a garden at a maximum security facility is provocative: why should people who committed these violent crimes be gifted with a garden? In thinking about this question, I was reminded of a story from my hometown some years back: a woman who as a teen had violently murdered a child; the ultimate unforgivable crime. Years later in prison, it turned out she had an astonishing gift for training service dogs for the disabled. And somehow the mother of her victim found it in her heart to donate a dog to the training program in her daughter’s memory, to be trained by her daughter’s killer. From the worst possible place comes a belief that yes, through something beautiful and restorative, we can listen to the better angels of our nature.

From deprivation comes inspiration. These words were spoken by Hoichi Kurisu, whose magnificent work graces landscapes across this country and whose career has connected him to our garden for about half a century. Yet on that day he spoke to us not as a prolific and acclaimed landscape designer but as a member of a team: humbly telling the story of how a prison community can collaborate to make something we might well call a garden of redemption.

–Kristin Faurest, Director, International Japanese Garden Training Center